Multi-Tenancy

Multi-Tenant or Multi-Tenancy means that a single instance of the software and its supporting infrastructure serves multiple customers. Each customer shares the software application and also shares database/schema/table. Each tenant's data is isolated and remains invisible to other tenants.

Net Core Genesis' default behaviour is Table-based multitenancy.

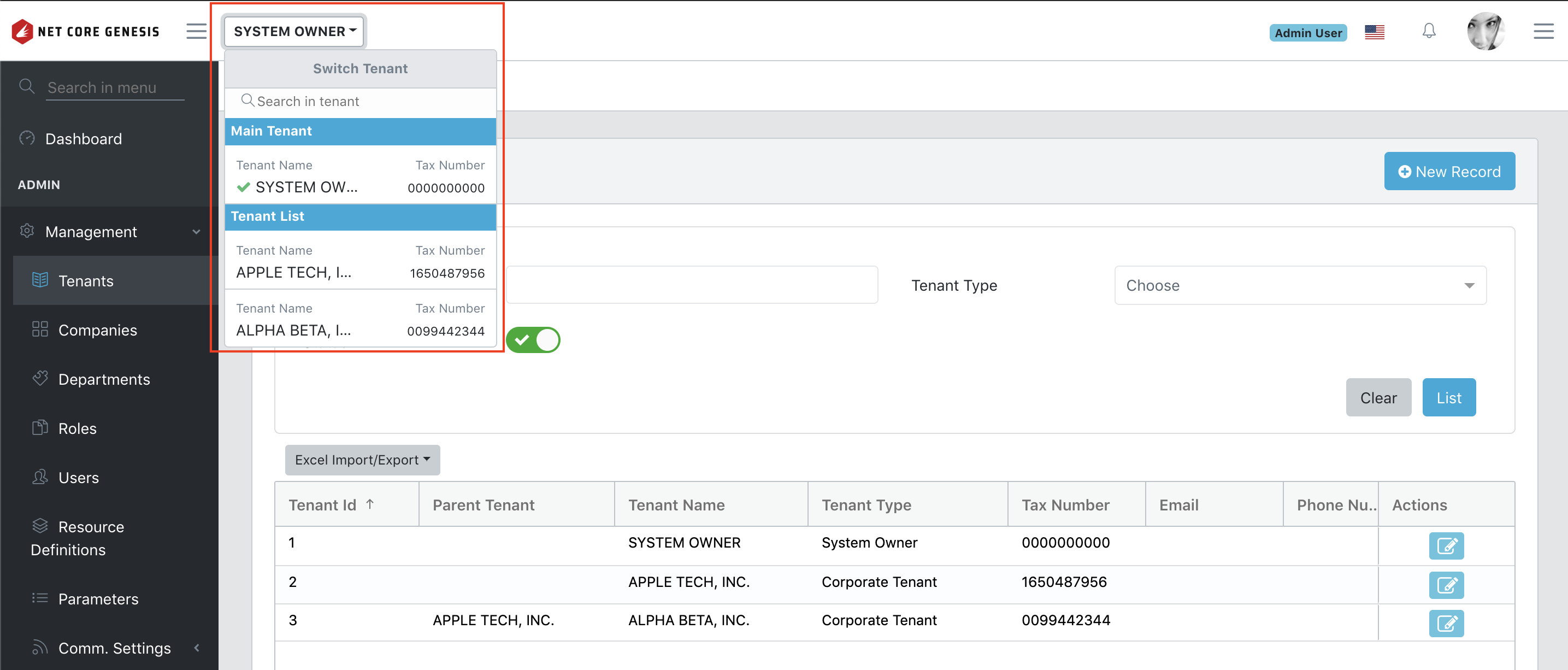

Switch to a Subtenant

1) DB

Every table that serves as multi-tenant must have the column named tenantId (int). You can customize it according to your needs in CoreType.DBModels.ITenantInfo.

2) Backend Models

Every model that serves as multi-tenant must inherit CoreType.DBModels.ITenantInfo which has TenantId.

3) Repositories

TenantId is added to each repository and query (insert, update, delete, get, list) automatically.

To customize the behaviour, go to

Base.CoreData.Common.ContextBase.cs

How to disable multi-tenancy for a specific case?

Use IgnoreQueryFilters

Sample:

res.List = context.Set<SomeEntity>()

.IgnoreQueryFilters() // This line prevents TenantId to be added to SQL script's Where condition

.AsNoTracking()

.Where(someEntity => someEntity.AssignedUserId == Session.CurrentUser.UserId)

.AddFilters(entity)

.AddSortings(entity)

.ToPaginatedList(entity);

An alternative way to store connection strings is defining them in appsettings.json for each tenant

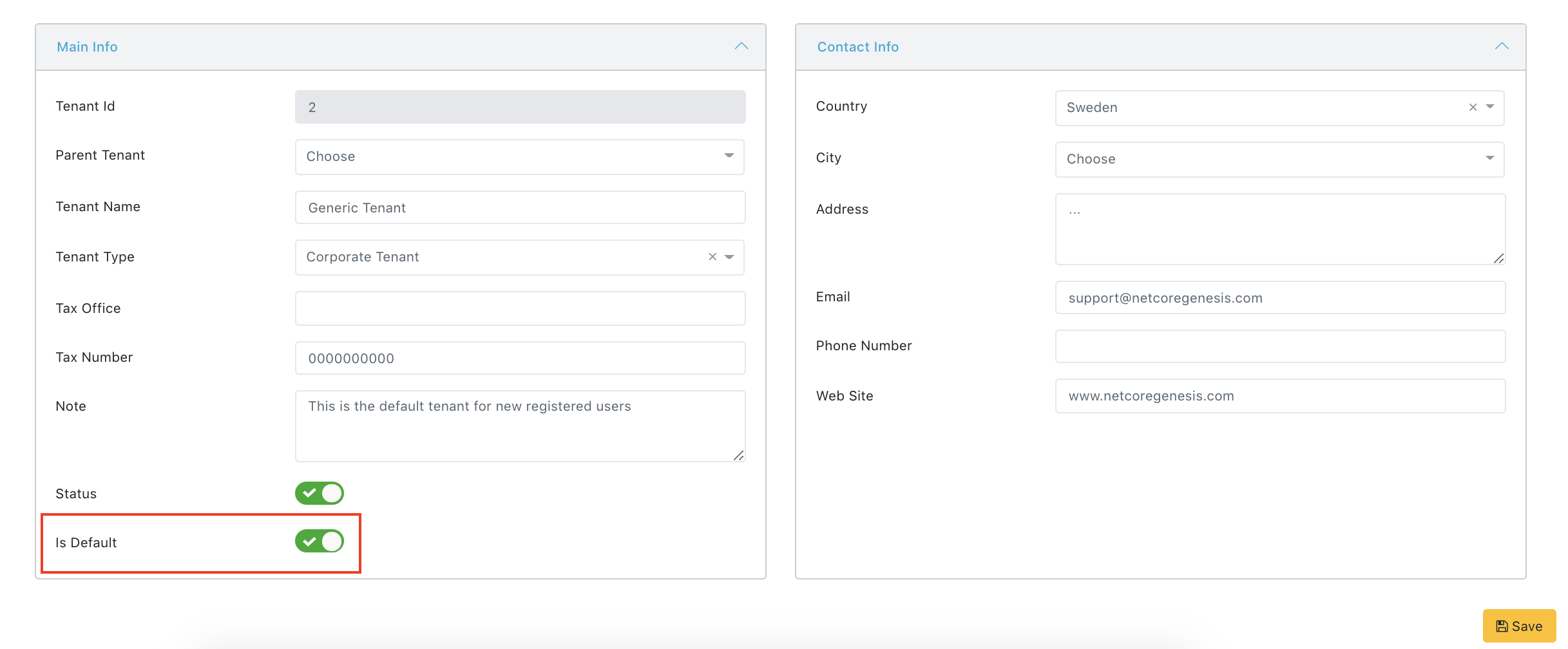

Can default Tenant be set for new registered users?

Yes. Just set "Is Default" to on/true in Tenants page.

Can default Role be set for new registered users of a tenant?

Yes. It can be set for each tenant separately in Roles page

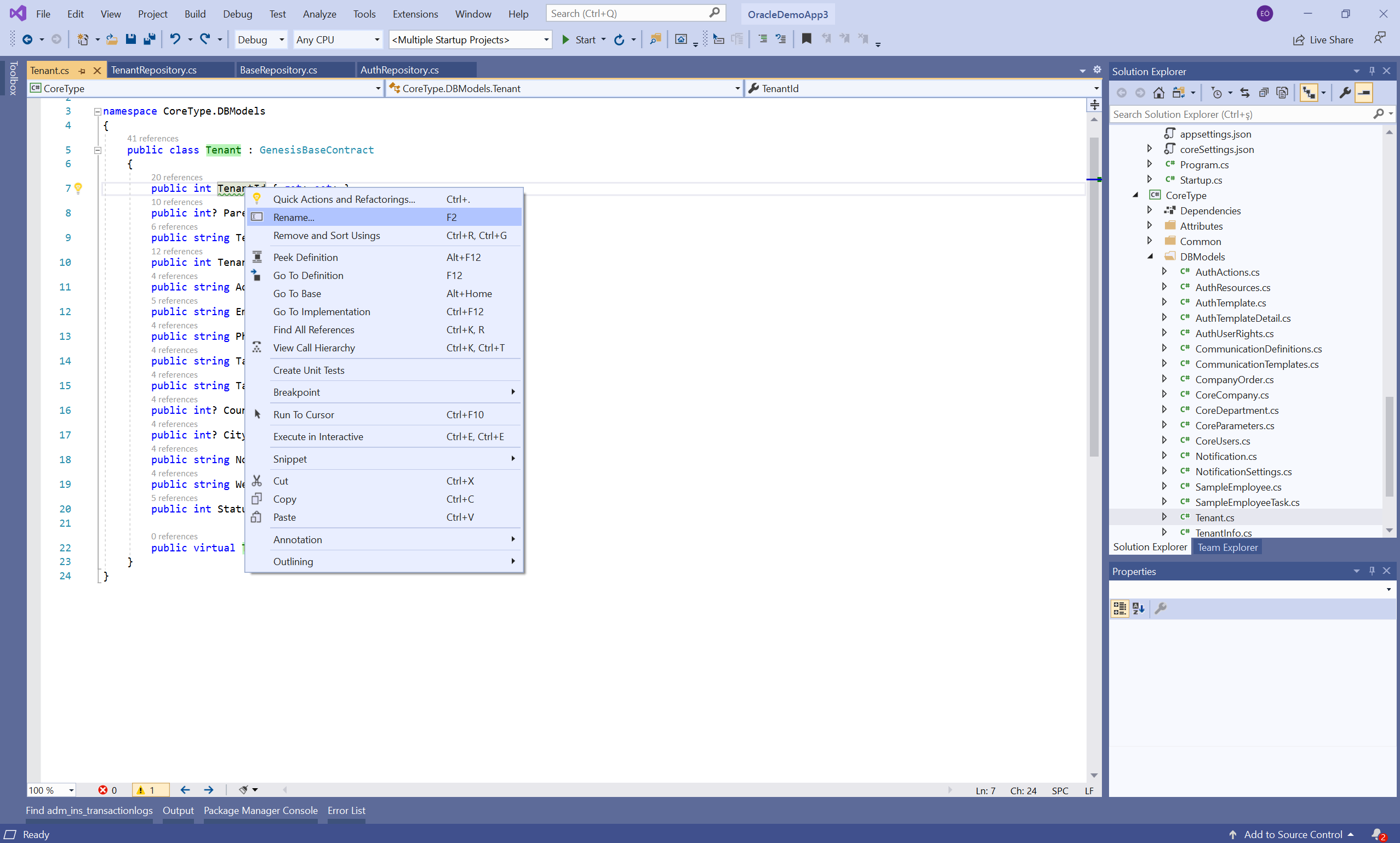

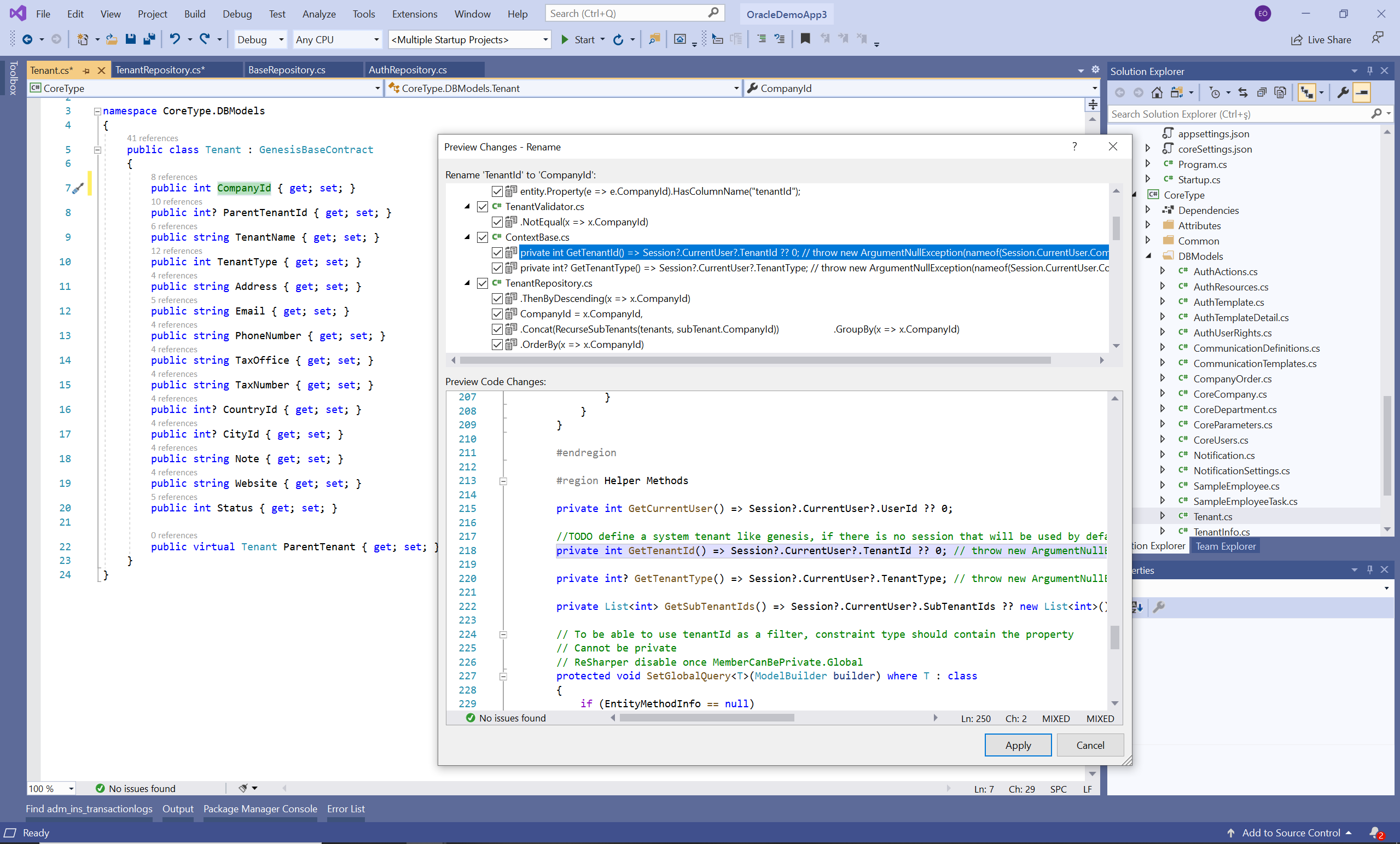

What is the best way to rename TenantId to something else such as CompanyId?

Let's assume you use Visual Studio;

Please note that Tenant and User email addresses should be unique

What if I want to manage multi-tenancy in separate databases or schemas instead of just tenantId?

You can change connection strings in context according to the tenant.

A relational database system provides a hierarchy structure of objects which, typically, looks like this: catalog -> schema -> table.

Let's see how we can use each of these database object structures to accommodate a multitenancy architecture.

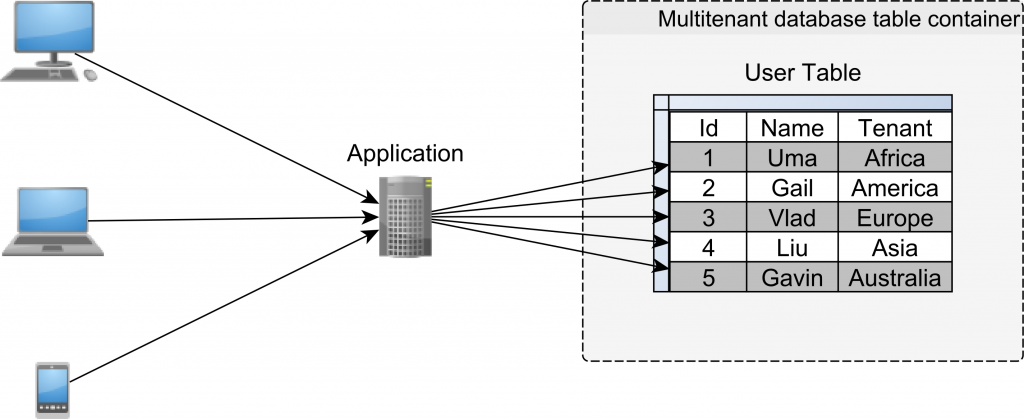

a) Table-based multitenancy (default behaviour of Genesis)

In a table-based multitenancy architecture, multiple customers reside in the same database catalog and/or schema. To provide isolation, a tenant identifier column (tenantId) must be added to all tables that are shared between multiple clients.

Pros: On the operation side, this strategy requires no additional work, the data access layer needs extra logic to make sure that each customer is allowed to see only its data and to prevent data leaking from one tenant to the other.

Cons: Since multiple customers are stored together, tables and indexes might grow larger, putting pressure on SQL statement performance.

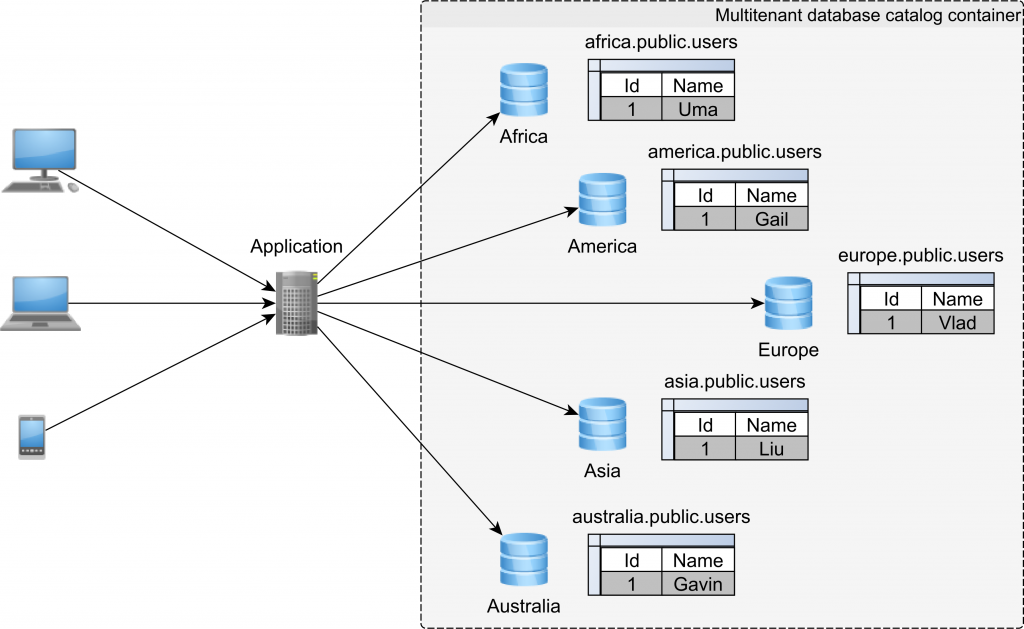

b) DB/Catalog-based multitenancy

In a catalog-based multitenancy architecture, each customer uses its own database catalog. Therefore, the tenant identifier is the database catalog itself.

Pros: Since each customer will only be granted access to its own catalog, it’s very easy to achieve customer isolation. More, the data access layer is not even aware of the multitenancy architecture, meaning that the data access code can focus on business requirements only.

This strategy is very useful when using a relational database system that doesn’t make any distinction between a catalog and a schema, such as MySQL.

Cons: The disadvantage of this strategy is that it requires more work on the operations side: monitoring, replication, backups. However, with automation in place, this problem could be mitigated.

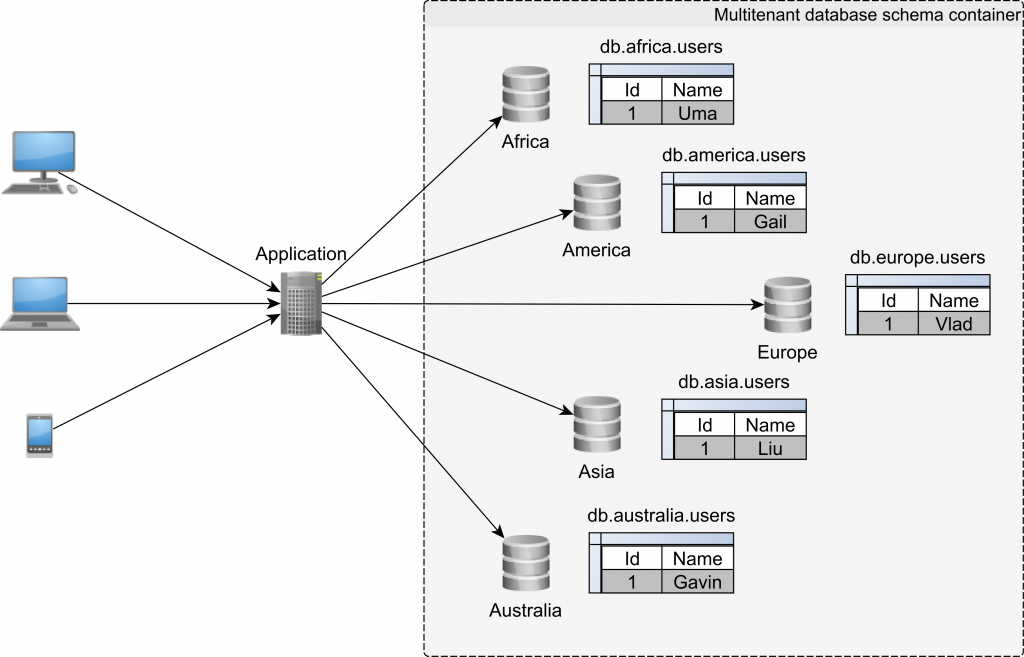

c) Schema-based multitenancy

In a schema-based multitenancy architecture, each custom uses its own database schema. Therefore, the tenant identifier is the database schema itself.

Pros: Since each customer will only be granted access to its own schema, it’s very easy to achieve customer isolation. Also, the data access layer is not even aware of the multitenancy architecture, meaning that, just like for catalog-based multitenancy, the data access code can focus on business requirements only.

This strategy is useful for relational database systems such as PostgreSQL which support multiple schemas per database (catalog). Replication, backing up, and monitoring can be set up on the catalog-level, hence all schemas could benefit from it.

Cons: However, if schemas are colocated on the same hardware, one tenant which runs a resource-intensive job might incur latency spikes in other tenants. Therefore, although data is isolated, sharing resources might reveal performance issues.